Lounging nude in a bathtub, George Brummell holds a razor to his throat. Will he remove his stubble, or end his life?

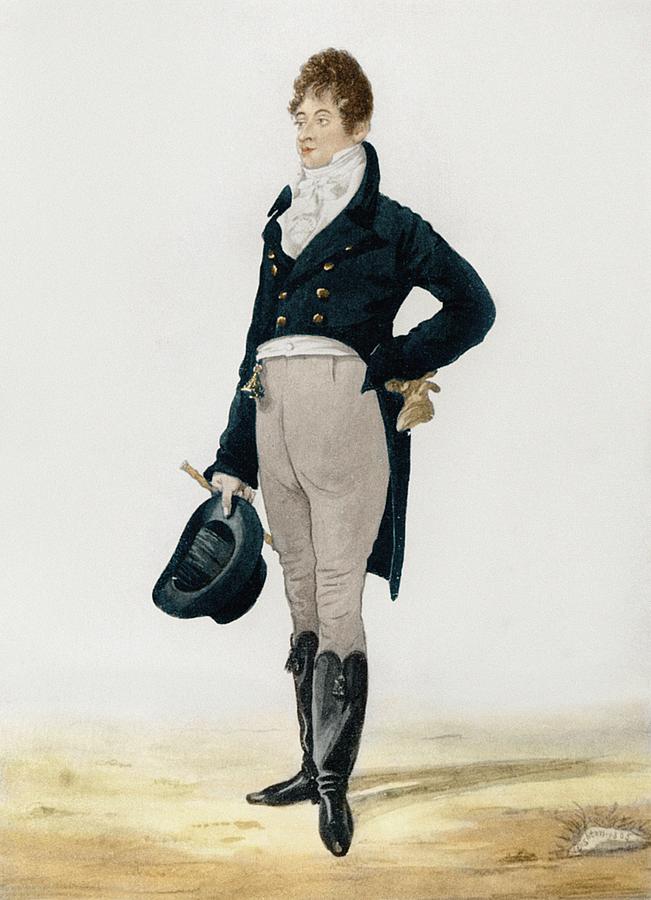

This stark suicidal pose we opens Ron Hutchinson’s semi-biographical play about the life of Brummell, starring Ian Kelly. I quickly feared a sensationalized portrait of a madman, but this was immediately assuaged by the wit and rapport between Brummell and his fictional valet Austin, the only two characters in the play. Kelly is of course the author of the recent highly acclaimed biography of Brummell. The valet, played by Ryan Early, is a well developed character in his own right, and is used as a rational foil for Brummell’s idealistic eccentricities. Throughout the production Brummell dresses and undresses, allowing the viewer to experience a metaphorical “revelation” of sorts, candidly privileged to see the famed dresser undressed.

The action takes place on one day close to the end of Brummell’s life when he is living in poverty in Calais. The occasion is special because King George IV, who as Prince Regent had been Brummell’s close friend and benefactor, is passing through Calais. Much of the play focuses on Brummell’s famous “Who’s your fat friend?” insult, blaming much of Brummell’s downfall on that fateful line. This reduction of the myriad complex reasons for Brummell’s exile to one bon mot might be factually inaccurate, but in the context of the play beautifully illustrates the man’s priorities and core beliefs.

A legitmate concern is that Ron Hutchinson’s play would try too hard to draw parallels between Brummell’s world and today, such as comparing a true individual of stylistic genius and originality to the off-the-peg, store-bought and ultimately sterile trend of metrosexuality. As Dandyism.net’s Nick Willard has mentioned in his review of Kelly’s bio, the hype surrounding this resurgence of Brummell-related studies is off-putting to anyone genuinely interested in the history of dandyism. The constant attempts by marketers to proclaim Brummell an early example of today’s cult of celebrity (for example, the overused declaration that Brummell was “famous for being famous”) can often seem to relegate Brummell to the level of a celebutante, instead of the original, fascinating man he was.

Hutchinson’s play, however, succeeds in showing the depths of Brummell’s nature and his neverending conflicts and contradictions of character. If the play succeeds masterfully at anything, it is placing Brummell in the context of his times. While his contributions to style, fashion, and wit are often obvious, the play goes deeply into the complex and often contradictory attitudes toward class which are presented by Brummell’s unique position.

Brought to light through the interaction with his valet, as well as his venting of his opinions of the king, we see Brummell’s stance vacillating between an egalitarian point of view and a firm belief in class mobility. For example, Brummell speaks of his father the state official when it suits his purpose. However, he just as easily calls upon the working-class credibility of his grandfather the valet. In addition, the play illustrates the interesting fact that someone of Brummell’s class background was able to ascend as high as he did in society and exist socially, if only for a time, on a level equal to that of the prince.

In addition to the class aspect of Brummell, we are shown how he is a figure marking several turning points: the end of an age of elegance, the beginning of industrialization, and a sartorial shift toward subtlety and dignity. Brummell’s utopian visions of all men spending their time dressing instead of fighting might appear naive and irrational, chiefly because such views are no longer unique. However, in him these ideas reflect an almost existential philosophy. Brummell declares that because life is so fleeting and actions have such little meaning, the only way to overcome the futility of life is to make it pleasant through beauty. And, as is so crucial to any understanding of dandyism, Brummell teaches the audience that creative productivity (i.e. painting, writing, sculpture) of any kind is not a necessary component of art. Brummell preaches that life itself can be the ultimate work of art.

The theater was filled with the usual demographic of New York City off-broadway theater-goers: somewhat confused-looking white middle-class octogenarians from the suburbs. Listening to them talk to one another, it was clear that few had any idea of who Brummell was, and that most of them were there simply because they wanted something to do in order to keep themselves active. One must realize that the real test of the play is not only whether or not it meets with the approval of students of dandyism, but whether the rest of the audience would walk away with some deeper understanding of a subject who has been trivialized by many.

When the play ended, I overheard audience members discussing how much they had learned, and one gets the sense that they were now able to feel a newfound sympathy for the man without declaring him wholly pathetic. To be sure, the Beau had many problems, many surely of a psychological nature. Both Hutchnson and Kelly manage to accurately portray Brummell’s neuroses and uncertainties while admirably preserving the dignity of the man who created such a vital art form and lifestyle.

Mr. Kelly’s next project (now in post-production) is a BBC film version of his book, which, if half as good as this play or his biography, could well turn out to be known as the definitive Brummell film. — NATHANIEL ADAMS

Rather late in the day to be responding and thanking Mr Adams and Mr Willard for taking such precise and informed interest in Brummell, the biography I wrote, and the play in which I appeared in New York nearly tao years ago. I was checking something online on a new work, on Casanova, and came across these listings. I wish the standard of informed reviewing was as high everywhere; it was an honour to be involved in the research and writing, and indeed, the playing of such a complex and compelling individual; even Casanova can seem thin sometimes in comparison. Hoping still one day to reprise the role, over here or again the States. Do look out for Casanova, with Penguin the US, this autumn. With all best wishes and thanks: I am converted fan of your site! Ian Kelly

I’m glad to have caught the original production back in 2001; despite, or moreover because of my bare notion of ‘dandyism’ and still scanter sense of historical context. Indeed the notion itself is what really matters.

And that said, it’s been a fresh pleasure to have recently read Ron Hutchinson’s play with the biographical knowledge which has since been bestowed by Mr. Kelly. The play pre-dates our scholar’s revelation with regards the syphalitic dementia which claimed Brummell’s sanity in that his valet asserts , “You were in debtor’s prison and it sent you mad.”

There’s also an interesting departure from the stoic resistance to suicide which biographers have attributed to Brummell; all the more interesting in that Mr Kelly is prepared to share the emphatically alternative scenario of Brummell being unable, rather than unwilling, to put an unnatural end to his newfound nightmare existence.

Such speculation aside, the real wonder within Hutchinson’s work remains the believability of his subject (and indeed that of ‘Austin’ the revolutionary valet) ~ for although the usual handful of hackneyed sayings arise, the extrapolation is in itself convincingly Brumellian. Where the audience/reader is informed, ‘I once ate a pea. I have no intention of repeating the experiment.’ – it seems as though Hutchinson has imbued a rather threadbare epigram with the actual voice of its purveyor.

As to the now triumphant BBC drama; it really raises and superbly answers the question as to what made the Beau stand out from his style-seeking contemporaries in the dandy stakes. Indeed, it seems more than probable that Brummell’s influence was mainly sought due to the overwhelming mediocrity of his fellows. We know that Lord Alvanley was an accomplished wit and doubtless others had a flair for tying the stock, or may have been gifted with congenital dandy stature of the period. However the whole act only seems to have come together in Brummell himself while others who may have exuded effortless dandy credentials simply preferred to sip their port and squander their fortunes away from all the regency gossip, perhaps?

The 2009 production suggests as much; or at least in that apart from James Purefoy’s portrayal of the Beau and Mr. Kelly’s own urbane presence there was but one other quintessential dandy among the awkward crowd of aspirants. Look out for Nicholas Rowe’s performance as Lord Charles Manners the next time you take a leisurely look at that splendid interpretation of regency dandyism … we may never know the reality of those unique times but sometimes a sense of their sensibility seems to seep our way.