When Dandyism.net launched in 2004, we stated as our mission the desire to rescue the dandy from the slag heap of history through rigorous scholarship and unflinching self-righteousness. Now it is time to rescue one particular dandy: Lucius Beebe, an all-but-forgotten American original who barely warrants a mention by the academics of dandyism, who are more concerned with muddled abstractions like “performance” and “self-invention” than the tangible plumage of top hat and tails. To Beebe, this plumage was essential as it was to Fred Astaire. In donning it, Beebe simultaneously defined himself, an era, and the new genre of celebrity journalism. His gold-headed cane cut a wide swath through stuffiness, social conventions, and hoi polloi (he was called a notorious “peasant baiter”). Beebe’s patrician style was unmatched, as was the notoriety his wardrobe brought him. During his lifetime he was equally as famous as the stars and socialites who populated the small and swank universe he called “crazy luxe,” but within a few years of his death in 1966 he all but disappeared from public memory. Robert Sacheli ransacked a bevy of buried texts on Lucius Beebe in preparation for what is certainly the freshest and most thorough account of the man written in many decades. We encourage faithful myrmidons to join us in a toast to Sacheli for his assiduous research, and to a long-lost member of our fraternity. Welcome back, Lucius.

* * *

On a beautiful cloudless afternoon in San Francisco in the late 1930s, there were probably hundreds of luncheon parties being thrown, but only Lucius Beebe could have thrown this one. The exact menu is unknown, but knowing Beebe it likely began with champagne, moved on to dishes rich and rare, and concluded with cognac and cigars. Then, to clear the meal’s remains, Beebe later recounted, “We threw the eggshells and other incidentals on Mr. Hearst’s elegant San Simeon estate.” The luncheon, you see, took place on a Goodyear blimp. Among the clouds it was champagne, laughter, and eggshells aimed at America’s richest newspaper baron, while thousands of miles away the world prepared for war.

This is how Lucius Beebe spent his life: host of an endless moveable feast as untethered to the realities of time and place as that balloon floating above the Pacific coast. Beebe was a supreme example of the detached ironist laughing at the foibles of the modern world, but that vantage point came at the price of a kind of splendid isolation.

There was a time when Lucius Beebe was the most famous dandy in America. Fifty years ago, housewives in Fresno could tell you the number of suits in his well publicized wardrobe (there were 40). Commuters driving home to Westbury or Winnetka could describe the decor of his private railcar (Venetian Renaissance, complete with Turkish bath). And young men imagining a life beyond Springfield knew which of his lapel ornaments had been temporarily swiped by a socialite at a Noel Coward opening night (a diamond gardenia worth $10,000). But say his name today and you’ll likely be met with an expression as empty as a speakeasy raided by New York’s finest.

Beebe was an author, bon vivant, and unrepentant Tory; a connoisseur of fine wines, railroad lore and bespoke haberdashery; and, due in great part to his own indefatigable efforts, he was once a legend on the order of Beau Brummell, King Kong, or P.T. Barnum — notables with whom he shared not a few idiosyncrasies. At the heart of Beebe’s outsize personality were two characteristics he cherished above the rest. He was, according to his longtime partner, “an individualist and, by virtue of his own time machine, an Edwardian.” A Janus in a derby, Lucius Beebe was the first retro-eccentric dandy of the modern era, a distinction made more fascinating by the fact that 1.5 million readers once thought him the most up-to-the-minute man in New York.

You Must Have Been a Beautiful Beebe

Lucius Morris Beebe was born 1902 to a wealthy clan in Wakefield, Massachusetts, and his education was as notable for its peripatetic nature as it was for the quality of the institutions through which he passed. Amateur explosives and amateur drinking got him booted from the first two of his three prep schools. At Yale, where he lived in a room with a roulette wheel and a bookcase that revolved into a bar, his primary pursuits were nightlife and shocking classmates with his clothing. He also tossed off much verse of dubious quality, and the opening of one poem (“I am weary of these times and their dull burden/Sweating and laboring in the summer noontide”) shows that his nostalgia was already firmly entrenched. Very little sweat and labor clouded his own noontides, and he was known to appear at early-morning classes in the previous evening’s white tie and carrying a gold-headed cane, the effect enhanced by his lanky 6’4″ frame.

Drink once again hastened his departure from the halls of academia, though more indirectly this time. Outraged that a poll of Yale Divinity School students showed overwhelming support for the enforcement of Prohibition, he fired off a pseudonymous letter to the campus newspaper, a missive whose phrases (“out of the colossal cavity of their ignorance,” “innocent device that proved a pleasure to Jesus Christ,” “exhibit their poltroonish idiocy,” “Such whim-whams we may look for in pretzel-varnishers,” “dodos and dinosaurs at large on the campus”) hint at the arabesques of prose that would come to characterize his writing career.

The dean of the Divinity School made his disapproval known to Beebe, who later tried to get the last word by rising in a box at a local theater, resplendent in fake whiskers, and announcing “I am Professor Tweedy of the Yale Divinity School,” before lobbing an empty liquor bottle on the stage.

Yale had the last word, and it was “goodbye.”

After a year on a Boston newspaper, Beebe packed up his poetry notebooks and canes and headed to Harvard, where the muses and the high life continued to call in equal volumes. Wolcott Gibbs, in a delightfully cockeyed 1937 New Yorker profile of Beebe, captures the undergraduate dandy: “When his father was amiable and funds were high, he ate magnificently at the Touraine — he wore a monocle, and was embarrassed when it fell into the soup and had to be fished out and dried by a waiter.”

Graduating in 1927, Beebe continued studies at Harvard, focusing his graduate thesis on the work of poet Edward Arlington Robinson. As part of his research, Beebe borrowed from the poet the manuscript of deleted sections from one of his works but found more than just a scholarly use for them: He had them printed as a limited-edition volume of 17 copies. When a fellow student alerted Robinson of Beebe’s publishing operation, the writer and Harvard were understandably concerned. Beebe confronted the tattletale in his rooms. Gibbs recounts that “a heavy bookcase fell or was thrown,” causing serious injury to the man, and “Harvard, not unreasonably adverse to being the scene of a trial for manslaughter, took action promptly, and for the second time Lucius was a martyr to culture.”

Dateline Babylonia

After a sojourn at another Boston newspaper, in 1929 Beebe was hired by the New York Tribune at $35 a week, and at first it looked as if he’d last about as long there as he did at one of his prep schools. Factual reporting of the more mundane events and calamities of urban life did not inspire his pen. He was known to attend fires in morning dress. Switching his beat to theater and movies proved equally unpromising. He called Hollywood “the outhouse civilization of the world, full of preposterous mountebanks and bores who live in the most witless and spurious manner ever devised.” He also filed interviews with performers in which, according to Gibbs, “it could be observed that the subjects, both men and women, spoke in an educated and haughty manner, rather reminiscent of Mr. Beebe himself.”

In 1933, the manager of the Herald Tribune‘s syndicate found a subject that was the perfect match for Beebe’s singular personal and journalistic styles: New York life itself — specifically, the part of it that was riotously conducted between sunset and the appearance of the milkman. The general idea was to chronicle the city as “a Babylonia-on-the-Hudson, sinful, extravagant, full of the nervous hilarity of the doomed,” says Gibbs, and no more ideal scribe could be found than that “richly upholstered Babylonian” from Wakefield.

Beebe’s timing was as impeccable as one of his evening emsembles. The long cocktail party of the 1920s and the hangover of the early years of the Depression had played havoc with the old-style status quo, and New York saw the emergence of a new kind of elite, a spangled crowd that came to be known as Cafe Society. Though the term itself was initially spun by columnist Maury Paul (who wrote under the name Cholly Knickerbocker), it was Beebe’s syndicated column “This New York” that made it a household phrase for glamor-hungry readers from Philadelphia to Seattle (and, for several months, a few bewildered ones in Ketchikan, Alaska, whose local editor took on the column not fully aware of its content).

In contrast to the old-money crowd that dominated New York society for generations, Beebe explained that Cafe Society was a very modern phenomenon. It was the product of journalism in which gossip and scandal were increasingly important components, and a byproduct of a city where being seen, particularly at the burgeoning number of smart nightspots, was more important to celebrity than simply being rich during daylight hours. Cafe Society, as he defined it, was “an unorganized but generally recognized group of persons whose names made news and who participated in the professional and social life of New York available to those possessed of a certain degree of affluence and manners.”

So goodbye Mrs. Astor, hello Tallulah Bankhead.

Beebe provides a run-down of what filled the calendars of the set’s glamor girls, entertainers, debs, and the well dressed and well funded of both sexes:

It was this amiably demented whirl of scrammy entertainments, Elsa Maxwell levees, Fifty-second Street morris dancing, whoopsing, screaming, and clogging it to Eddie Duchin music at the Persian Room of the Plaza, making pretty faces for the camera at Gilbert Miller first nights, bicycling through Central Park to charity carnivals, keeping luncheon trysts at the Vendome in Hollywood and being at the old desk next morning, gossiping by the hour on the London phone, and living in a white tie till six of a morning before brushing the teeth in a light Moselle and retiring to bed, which constituted the life of Manhattan’s cafe society.

There was no more energetic proponent of whoopsing, screaming, and clogging than Beebe himself. To his readers, the columnist became inseparable from what he dubbed “crazy luxe,” the near-mythical milieu that he covered and in a large part created. But the Beebe who spent his nights at 21, the Stork, the Colony, El Morocco, and the Rainbow Room was also a man who longed for the vanished, gas-lit world of Delmonico’s. Gibbs paints Beebe as possessing “the true Bourbon’s profound hostility to change, looking much more affectionately on the decent past than any raw new world to come.” Beebe later stated it simply and directly in a recollection of the well mannered Boston of his childhood, extending his judgment to the London, Paris, and New York of yesteryear: “Everything everywhere was better then, and the measure of all worldly wisdom attests to it.”

Despite the creative innovators who filled his circle, Beebe’s tastes in art, music, and literature were profoundly conservative. Modern forms of writing “depressed and confused him.” He covered the 1934 opening of the Virgil Thompson-Gertrude Stein opera “Four Saints in Three Acts” and promptly pronounced it “the fanciest and most utterly Bedlamite flag-raising within recent memory.” Airplanes were forever “the Wright Brothers’ folly,” and equally foolish were travelers who strapped themselves into these “hurtling tubes of death.” The first of his many volumes on the romance of train travel appeared in 1938, and Time sniffed “that so soigné a soul as Lucius Beebe should ride a hobby as undandified as railroading is as unlooked-for as red wine with fish.” That paradox, however, was Beebe’s greatest party trick. He was the only man who simultaneously managed to be a citizen of the New Yorks of Gypsy Rose Lee and Edith Wharton.

Setting The Style

Dressing for the role of official czar of Nightclubland came naturally to Lucius Beebe, as he’d been rehearsing for it all his life. Beebe was reportedly the first man to introduce white linen plus-fours to Yale (Gibbs reported that “Professor Chauncey P. Tinker, seeing them at a distance, complained irritably that the place was getting overrun with women. ‘Don’t look now,’ he said, ‘but here come two of them now.'”) He got better reviews from his fellow students. The campus paper enthused over his “orchidaceous grey trousers” and “vine-covered top-hat.”

In London, Beebe ordered his suits from Savile Row’s Henry Poole & Company, and he looked on being measured for a bespoke suit as something akin to taking the sacrament. The venerable gentleman’s tailor was “not only a cathedral of waistcoats and hunting pinks, [but] a repository of Victorian grandeurs establishing continuity with the past and the great names of English legend.” Throughout his life, his business suits from Poole duplicated the lines of one made for him in New York in the early ’20s, which were, he says, “cut from doomsday fabrics, with notched lapels and four buttons.” The suits were only one component of the grand effect. The New Yorker helpfully provided its readers with a partial inventory of Beebe’s dressing room:

He has a good evening dress coat lined with mink and collared in astrakhan, which he has insured for $3,000, and an old rag also lined in mink, but with a sable collar, which didn’t seem worth the bother. The jewels necessary to set off this splendor, or else hold it together, include three gold cigarette cases (although he rarely smokes anything but cigars), valued at $700 each [in 1937 dollars], a cashmere sapphire cabochon ring worth $1,200, a single emerald stud at $500, and a platinum evening watch which cost $10,000.

Though Beebe thought of formal clothes “quite literally as the livery of my profession,” he disingenuously complained that “Walter Winchell and other scoundrels” had so unfairly pegged him as “a dude among the legmen, a penny-a-liner of vast and effulgent sartorial resource” that it “became necessary for him to lay in a stock of tail-coats, Inverness cloaks, and collapsible top hats to live up to the legend.” Things had gotten so out of hand that “as time passed it was impossible for him to identify himself at his bank unless he was wearing court attire complete with orders and a dress sword.” (The third-person voice was typical Beebe. Using the first person apparently came off as too chummy.)

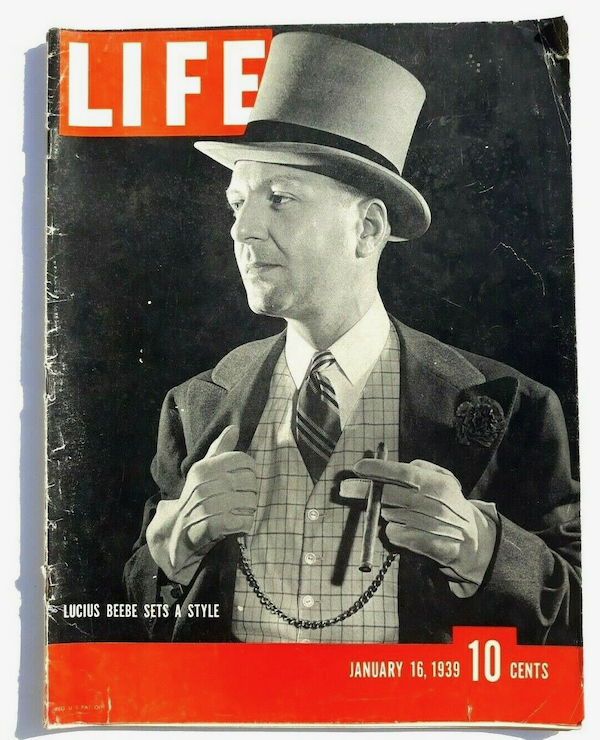

In February 1939, Beebe was feted as a male fashion leader at a luncheon thrown by the gentlemen of the National Association of Merchant Tailors of America, but the shindig could have been considered somewhat of a comedown. A few weeks earlier he’d received a wider, if more populist, accolade on the cover of Life magazine. “Lucius Beebe Sets a Style” was the line that accompanied the photo, in which all his trademarks were on view: the top hat, boutonniere, leather gloves, checked waistcoat and antique gold chain, as well as a panatela and an expression falling somewhere between resigned boredom and regal condescension. In truth, Beebe’s style influenced no one at all in the real world, except possibly carnival barkers or costumers of operettas.

Unlike the Duke of Windsor or Fred Astaire, personalities whose now-classic styles of the 1930s are still admired and emulated, Beebe as a dandy was sui generis, which most likely was just fine with him. Though the relaxed and colorful resort wear worn by members of the Palm Beach set (bush jackets, striped blazers, polo shirts, and light-hued dinner jackets) featured inside that Life issue still looks modern and stylish, you can bet that Beebe wouldn’t have been caught dead in any of it.

Hoofers and Philosophers

While tailors and much of the popular press applauded, Beebe and his wardrobe were not always kindly treated in print. He was simply too tempting a target. “Orchidaceous” got trotted out regularly, as did “rococo,” “baroque,” and “mauve elegant.” He was unaffectionately tagged “Luscious Lucius” by Walter Winchell. “Beaunash,” the writer on male fashions for Playbill told the New Yorker‘s “Talk of the Town” reporter that he found Beebe very badly dressed indeed.

Much of the adjective-based innuendo hinted that Beebe was gay — which he nonchalantly was. “Lacy Jones” was the Time headline for a review of his first railroad book, and even as indulgent an interviewer as Wolcott Gibbs found it necessary to note, “his friends would be a little startled if he married.” In a sense he did. In 1940, Beebe met Charles Clegg at a Washington house party given by Evelyn Walsh McLean, and the two were a couple — remarkably openly for the times — from then on. That he met the man who shared his life while wearing the Hope Diamond as a gag seems somehow fitting.

Despite the catcalls from some quarters, it’s nearly impossible to overstate the influence that Beebe’s personality had on the popular culture of his times. In 1938, the Chicago Ballet served up a concoction called “Cafe Society” in which the “thickly disguised” (as Time put it) main characters included prizefighter Max Baer, dime-store deb Barbara Hutton, and naturally Beebe himself. Beebe’s name provided the punch line for countless cartoons, which often featured hoboes with pretensions. Throughout his career he happily shilled for products seeking connection with the bon ton, from scotch to Studebakers.

D.net has already spotlighted what’s undoubtedly the only dancing tribute to a dandy, Harold Nicholas’s spectacular “Mister Beebe” number from the 1944 musical “Carolina Blues.” Nicholas appeara in a costume that echoes Beebe’s Life cover get-up, and the song includes the observation, “It’s also said when he goes to bed/His pajamas are as groovy as a Technicolor movie.” They most likely were.

Five years earlier, Beebe made a cameo appearance in a vehicle called “Cafe Society” in which reporter Fred MacMurray romanced heiress Madeline Carroll, and for which, to Cholly Knickerbocker’s consternation, he pocketed $500 from Paramount as the inventor of the title. “It achieves the almost incredible distinction of libeling its subject” was one critic’s verdict.

Beebe’s style became the sartorial shorthand for film and theater characters that were waspish, sophisticated and somewhat effete. In his homburgs, gloves, and fur-collared overcoats, majestic George Sanders in “All About Eve” is a flattering dead ringer for Beebe. Clifton Webb’s well-groomed but acid columnist Waldo Lydecker in “Laura” reflects a less savory side of an urban dandy, and even though based on Alexander Wolcott (a notably poor dresser), Sheridan Whiteside, the titular “Man Who Came to Dinner,” reflects some of Beebe’s worldliness and hauteur as well as a penchant for florid smoking jackets.

It was inevitable that Beebe would show up among the smart names dropped in a Cole Porter list song, and so Ethel Merman in “Panama Hattie” belts “When I give a tea, and Lucius Beebe ain’t there/Well, I still got my health, so what do I care!” The classiest tribute came from Broadway lyricist Lorenz Hart. For the show-stopping song “Zip!” from “Pal Joey,” in which a deep-thinking stripper unveils the range of her cerebral interests, he created the timeless triplet, “I adore the great Confucius/and the words of luscious Lucius/Zip! I am so eclectic.”

In 1940, Beebe probably had an edge on the philosopher in the fame department, and certainly was the better dressed.

Western Sunset

World War II brought changes even to Beebe’s world. Charles Clegg enlisted in the Navy soon after Pearl Harbor, more uniforms than dinner jackets were seen in the swankest nightclubs, and Carino, the incomparable maitre’d at El Morocco, was asked to bend wartime rationing rules by a socialite’s request to “just bootleg me a little black coffee in a cocktail glass.”

A bigger change came in 1950, when Beebe and Clegg waved goodbye to the “gobaloney golconda” of Manhattan and hit the gilded trail to Virginia City, Nevada. In a graceful valedictory written for Holiday magazine that year, Beebe allowed that he still loved city life, but “I am taking it on the lam for the same reason the wise guest goes before the party is over. The last part of every party is not the best.”

Beebe traded his top hat for a Stetson and the party moved a few thousand miles west. He and Clegg purchased the Territorial Enterprise, a paper founded in 1858 and noted for first publishing the stories of Mark Twain, to which, according to one observer, they brought “a zest and syntactical abandon unknown to the flaccid journalism of the East.”

During their years in Nevada, Beebe’s writings often sang the praises of the roaring days of the Comstock Lode, and the region’s colorful history gained a few new hues in his retellings. Preservation became one of his pet projects, and he was an avid watchdog for Virginia City’s civic affairs. His perspectives on urban planning could be unorthodox, but entirely in character. A bordello that planned to open next to a school caused a fuss among the citizenry, to whom Beebe proposed the obvious solution: “Move the school! Don’t move the girls!”

Naturally, Beebe and Clegg made news as much as they reported it. Their showcase was the Virginia City, a private railcar of such gaudy splendor that Beebe admitted that their travels often prompted locals to “think we’re with a circus. The freaks, probably. It happens everywhere we go.”

It had a 23-foot observation-drawing room, a dining room where 8 guests could dine as if at the Waldorf, a 50-bottle wine cellar, 3 staterooms, that small Turkish bath, and quarters for two staff. Beebe composed a pamphlet as a guide to the car’s fittings, and even a short sample shows the hubbub was warranted: “The crystal chandeliers in the observation-drawing room were purchased from Venice as was the baroque gold cherub mirror over the fireplace. The dining saloon’s gold veined diamond paneled mirrors were manufactured especially for the car in Italy… The ceiling murals were copied from those in the Sistine Chapel in Rome… ”

It was the elaborate stage set for another breathtaking scene in the ongoing Beebe pageant, as was, Wolcott Gibbs suspected, the whole rootin’-tootin’ landscape. Paying a return visit to his interview subject in 1956, he thought that:

…just as he did in New York, Mr. Beebe is intent on imposing an older and more jovial system of manners on a community not always quite sure of what was expected of it, and even occasionally hostile. In his fond imagination, everyone in that part of Nevada greets the rising sun with two ounces of bourbon and ends the day prostrate on a barroom floor, and gamblers, prostitutes, and quaint survivals of the roaring past disport themselves with terrible enthusiasm. The paper reports this gaiety conscientiously…

Wolcott had nailed Beebe once again as a retro-eccentric extraordinaire.

San Francisco

The television show “Bonanza,” set in Virginia City, was a gold mine for the town, but this fictional version of old Nevada was at odds with Beebe’s more rarified vision, and in 1960 he and Charles Clegg decamped for San Francisco. The column “This Wild West” became his bully pulpit at the San Francisco Chronicle, and he continued to write for the glossy magazines that guided aspirants in the art of finer living, such as Gourmet, Holiday, and Town & Country.

Beebe’s work of this period still reflects his wit, enthusiasms and indulgences, but the charm could now sometimes curdle and the nostalgia grow overbearing. Still renowned as the nation’s foremost “eatall and tosspot,” Beebe roamed the globe and reported on fabled restaurants, but his articles blur into an over-rich banquet of le hommard Deauvillaise, poularde sautee au Champagne, croustarde de langouste, and soufflé Grand Marnier, washed down with Chateau Margaux ’34 and topped off with snifters of Hine cognac and a Cuban belicoso fino. Who, in the early 1960s, was dining like this?

And what other journalist was boasting that he had never seen a television broadcast, still railed against air travel, bemoaned the decline of the derby, or unironically asked in a column, “What Was So Wrong With 1905?” (For starters, its attractions did not include the disasters of “woman’s suffrage, the universal motorcar, credit cards, international airports, repudiation of the national currency, tranquilizers, freedom riders, digit dialing, and the one-ounce martini.”) A particularly nasty story about Bobby Kennedy appeared in the 1966 collection “The Provocative Pen of Lucius Beebe, Esq.,” and Clegg and a co-editor included it in a collection of Beebe’s works published in England a year after the senator’s assassination.

The mores and manners of the times were changing more quickly than even Beebe’s capacity for fantasy could counterbalance. A photo from this period shows a dandy in aspic, wearing an outfit that could have come from an actual Edwardian. The three-piece Glen Urquhart plaid suit, the droop of the heavy watch chain, the gloves, bowler, and the walking stick are all familiar. There’s also a bulldog-like hardness to his face, and the expression with which he stares out of the frame suggests he’s confronting the future with all the princely distaste he can muster.

Lucius Beebe died of a heart attack in 1966; he was 64. Charles Clegg followed, by his own hand, when he reached the same age 10 years later.

The Lost Dandy

Except to railroad buffs, for whom his volumes on the subject approach the status of sacred texts, Beebe quickly became a footnote to a dim and bygone era, a slightly entertaining but essentially irrelevant figure. Today, he’s all but forgotten among even the literate populace, and not a single one among his scores of books is available in current editions. That’s a shame, because Lucius Beebe still has much to say to us, and no journalist ever said it exactly the way he did. His prose style, like croustarde de langouste, may be an acquired taste, but the man can undeniably write and he’s funny as hell.

There’s real pleasure to be found in reading Beebe. His voice blends the argot of Shubert Alley, a newspapermen’s saloon, and a Vanderbilt drawing room circa 1905; the effect approximates a production of “The Importance of Being Earnest” as interpreted by the thespians of the Hot Box Revue. There’s the delicious surprise of encountering names like Hooper Hooper (who sported the most rakish silk hat in Boston), Basil D. Woon, Tipton Blish, Mrs. Albert Tilt, Mr. Reginald Stocking II, and Berry Wall, King of the Dudes, all of whom can be imagined slipping into the Stork from a parallel Wodehousian universe.

Beebe’s legacy as a names-make-news pioneer lives on, though what he’d make of its lurid and debased current incarnation is anybody’s guess (although it’s clear that he’d knock Matt Drudge’s pathetic little porkpie off his head with a quick swipe of a walking stick). Beebe’s writing offers insights into the games of fame and celebrity still played nightly. His article “Heels’ Progress” takes a sympathetic look at the young men (“dress-suit Okies” and “dinner-jacket hoboes”) who left Manhattan for Hollywood banking that their good looks, charm, or more intimate talents would land them on the screen or beside a producer’s pool, but who more often ended up behind the tie counter.

Then there’s the occasional passage that captures an era with the startling clarity and immediacy of a nightclub photographer’s flash. Beebe’s roster of the stag line at El Morocco (from a late-30s piece called “Who’s In What Saloon Now?”) is more than a collection of mostly-forgotten names; 70 years on, it has a melancholy beauty that recalls one of Gatsby’s guest lists:

Among them on a given evening might be seen Kip Soldwedel, a glittering young man of the boulevards; Jack Velie of Kansas City, nephew of Dwight Deere Wiman and one of the proprietors of the Deere plow works; Emlen Etting, the Philadelphia modernist painter; Bill Hearst and his young brother Randy; Delos Chappell, producer who revived the Central City Opera House in Colorado for a week’s run of “Camille,” which set him back two hundred and fifty thousand dollars; Winsor French, of the Cleveland Press, on a Manhattan jaunt; Bill Okie, display designer for a Fifth Avenue jeweler; “Junior” Wotkyns, a dazzling youth from Hollywood and the heart-throb at that moment of Libby Holman Reynolds; Quentin Reynolds, the fictioneer; Jack Kriendler of “Jack and Charlie” and “Mooey-Mooey” fame; Louis Sobol of the Journal, and Nat Saltonstall, most eligible bachelor of Boston, over for the week-end.

No other American cuts quite the same figure in the history of 20th-century dandyism. Beebe’s style, as outrageous as it could be, also had a courage and a liberating panache. He made men’s clothing a topic of popular discussion and saw himself as the embodiment of what every man might be if he simply dared. He told the assembled tailoring-trade types that had gathered for that 1939 luncheon in his honor that “Almost every man has either secretly or patently some feeling for clothes and would indulge his fancy far more lavishly and colorfully were it not for the jealousy, usually expressed in the form of sarcasm, by the women he encounters… No woman can stand seeing a man as well or painstakingly dressed as herself.”

But there’s also a cautionary strain that runs through the tales of Beebe’s dandyism. Though retro-eccentricity offers its charms, his life is a testament to the dangers it can ultimately hold for an adherent who has both the imagination and the means with which to indulge it. Wolcott Gibbs included one of Beebe’s more minor triumphs in his 1937 profile. In the days when the Central Park Casino was in operation, the management traditionally offered a magnum of champagne to the first person to arrive at its doorstep in a horse-drawn sleigh after the season’s first snowfall. An early-rising Beebe hired the sleigh of one Pat Rafferty from the Plaza cab bank and handily presented himself as that year’s winner. He was the single entrant. He had, in Gibbs’ lovely phrase, “raced with ghosts.”

The handsome youths in the stag line at El Morocco and the girls making the most of their entrances into the Colony have faded into the centuries-old New York night. The passing of decades and memory have rendered them as spectral as that lost city under the fresh snow. Lucius Beebe blazed a quicker route into the shadows. He spent a lifetime speeding — deliberate and hardheaded and magnificent — into the past, racing, as it turned out, with no other ghost than his own. — ROBERT SACHELI

Heaven

Blimp bash – I’m inspired!

Wonderful article.

Looking forward to the next installment.

Maybe it’s my plebeian ignorance, but I did not know Lucius Beebe was gay.

And, for once I can say this with no stigma attached…too bas he was gay.

Why is it too bad he was gay? Because no gay man can be a true dandy. A dandy must needs be a straight man since gay men frequently have that artistic/feminine edge making elegant presentation come almost naturally [another reason Oscar Wilde was no dandy]: a dandy must be able to pursue elegance and yet retain enough virility that were he to walk into a bar, a bully would think twice before mocking him.

G, I read your intriguing comment, thought about it carefully, and have decided I agree with you.

You suffer from plebeian ignorance.

Dear G~

You’re joking, right?

“a dandy must be able to pursue elegance and yet retain enough virility that were he to walk into a bar, a bully would think twice before mocking him.”

Um… Who a man sleeps with has no bearing on either his virility or his manhood. Beebe walked into many, many seedy bars in his time, including the Bucket of Blood Saloon in Virginia City — one of my favorite dives, BTW — with a kind of aplomb that most men, regardless of orientation, should envy. He was able to pull it off because he had style, could throw a punch and, like Wilde, hold his drink.

The idea that a gay man cannot be a dandy is the occidental uttermost of extreme absurdity.

M

Those who’ve visited G’s website thedandy.org and noted its content’s eerie similarities to D.net should congratulate him for finally coming up with an original idea.

M, Am I kidding? No.

For a man to be gay he must be attracted to his own masculinity, and not attracted to feminine aspects that would come naturally if he were straight. There is something, therefore intrinsically feminine about his nature; and thus it lacks something masculine. A gay man seeks masculinity and as such, he frequently needs to employ those feminine traits that “catch men” [and they seem to intrinsically understand and practice that; gay men frequently play out the “butch-femme” dichotomy in their private lives]. A dandy must be a straight man who appreciates elegance in a very masculine way, and who seeks to both seduce men and women socially with his manners: and women in particular romantically by being a refined man. I’m not saying gay men cannot do this, I’m saying gay men are out of the running. This because their natures give them an “advantage” in having that feminine “je ne sais quoi”, which frequently makes them more “effeminate”.

Christian:

Yes there are “eerie similarities” between our works. You will find that those who study the same subjects will frequently come to the same conclusions [were our mutual site dedicated to Astronomy you’d find we had the same measurements of Earth, Mars, and Venus: as well as the the same distances between them]. You will however notice that your on-line magazine is easily found from my work, while mine is unfindable form yours ,not that I would expect such since yours predates mine and excels it in every respect. I am nevertheless glad you find my observations unique.

And as for my suffering the ignorance of the plebeians?, I claim neither to be erudite, nor educated, nor particularly witty: I only claim to be well dressed.

As to my not knowing Mr. Beebe was gay; I wonder how many of your readers already knew that?

“You will find that those who study the same subjects will frequently come to the same conclusions.”

G. — Your site goes beyond reaching the same conclusions; it extends to using the same words, although I have to admit that you sometimes mangle them.

Your comment about claiming only to be well-dressed is, however, sufficiently witty.

“G, your use of logic makes bricology look like Aristotle.”

Oh, my! I must have been enjoying my claret a little too much last night.

G~: What a great fat lot of half-baked unschooled gobbledegook. As a psychologist of human sexuality you might consider taking up tennis, because you have absolutely no idea what it is that you are talking about. You sound like a complete buffoon and I am very disappointed in you.

While it’s interesting see how this has exposed prejudices — indeed plebian prejudices — this conversation should be about the many gems found in Sacheli’s excellent article and the rediscovery of genuine original.

For more of Beebe, if you go to http://www.epicurious.com and search under “Beebe” (not the recipe search, silly!) you’ll be able to view Beebe’s column for Gourmet magazine.

I understand G~ has a prejudiced mind, but plebeian?. Being a plebeian myself I cannot know.

“I claim neither to be erudite, nor educated, nor particularly witty: I only claim to be well dressed.”

Yet you talk like someone with knowledge or authority.

What a brilliant find, JES! Here’s a easier URL: http://www.gourmet.com/profiles/lucius_beebe/search?contributorName=Lucius%20Beebe

Excellent–thanks!

Michael, thanks for the sensible words. You, too, Nick and Christian. I have to admit I was concerned that some of the comments on my story have taken such and odd and distasteful course.

Then I happily realized that this mini-tempest in a martini glass was exactly the type of donnybrook that old Lucius would have relished. It simply shows that he’s a figure still capable of stirring up controversy. His choice words in that Yale letter are perfectly applicable to our correspondent: “colossal cavity of their ignorance…Such whim-whams we may look for in pretzel-varnishers…”

So, G., my top hat’s off to you for such a thoroughly entertaining exhibition of “poltroonish idiocy” that sadly demonstrates that the narrow-mindedness against which Beebe’s life stood in colorful relief is still with us, and reminds us that bold dandies like Lucius — no matter their orientation — are still relevant and necessary.

And by the way, your discussion of gender theory shows you have absolutely no clue about pretzel varnishing.

“Those who’ve visited G’s website thedandy.org and noted its content’s eerie similarities to D.net should congratulate him for finally coming up with an original idea.” Christian

That site is a bastard copy of D.net in many aspects. I am really disapointed with G~, I thought he was authentic enough to develop his own ideas.

Miguel Antonio writes: “Those who’ve visited G’s website thedandy.org and noted its content’s eerie similarities to D.net should congratulate him for finally coming up with an original idea.†Christian

That site is a bastard copy of D.net in many aspects. I am really disapointed with G~, I thought he was authentic enough to develop his own ideas.”

Miguel Antonio — I mean, Mr. Contes — you & I are finally simpatico.

Thank you, Mr. Willard. I felt like Julien Sorel in the Marquis de la Mole’s Maison my first time here in D.net, although now I think I am becoming part of the site. Or maybe I am lying to myself like Julien Sorel did in The Red and The Black?

Well my rant made much more sense the night I wrote it, probably due more to the bottle of Liebfraumilch that I was nursing than anything else [note to self, less Liebfraumilch, more Chimay]…oh well, there’s nothing like the taste of shoe leather..

Mr. Sachelli’s article is beautiful, and only makes one wish there were were more forms of media wherein one might appreciate work of such individuals as Lucius Beebe [someone aught to make a movie], I wonder [the article doesn’t say] if he was a flamboyant dresser like Wilde, or just had a fondness for accoutrements like monocles [which would already have been “old fashion’ in Beebe’s day].

As to my website, I did borrow the skeleton of D.net, but my site is not some rival work, it is a forum and resource for a club I belong to called the “Gentleman’s Society” whose favorite subject is dandyism. I had never created a website before and didn’t really know what format to use, so I based my site on a format I was familiar with, and appreciated- D.net [I’ve been reading D.net for almost 4 years now]. Perhaps I should make a few changes to make that more clear…?

G: Thanks for the gentler morning-after words and your appreciation of my article. I can assure you that there will be plenty of coverage of Beebe’s spectacular duds in the second of the three installments of the story. So stay off the Liebrfraumilch and stay tuned to D.net.

“Perhaps I should make a few changes to make that more clear…?”

G~

I think you should tone down your expert “status”. The site you made clearly shows that the emperor has no clothes.

How the estimable Mr Beebe’s homosexuality could have escaped anyone’s attention is beyond me, especially since so much has been written about him and his long-term relationship with the society photographer Jerome Zerbe. Even Walter Winchell made note of the relationship, noting that Beebe’s own columns might as well always end with the words “… and Jerome never looked lovelier.” That being said, a new biography of Beebe might be in order, between hard covers.

Miguel:

Um…I have never to claimed to be an expert in anything [in fact I avoid expertise at all costs].

I am generally only good for a laugh

I’m really intrigued by “the décor of his private railcar (Venetian Renaissance, complete with Turkish bath)”. Does anyone know where I can find out more about this, especially the Turkish bath. Credit will be given on the Victorian Turkish Baths website for any info used. Many thanks, Malcolm

Does anyone know that he had children?

I’m a blood relative of Beebe’s from my mother’s side of the family, Beebe being my Grandmother’s maiden name. I really appreciate the information in the article and glad people are again remembering his spirit of individuality. I’m realizing how much “Lucius” had come out in my personality and explains some of my unique clothing choices, my extensive hat collection (including several bowlers) and possibly even my 6’4″ frame. Anyway, thanks for the article. Marc.

Hey Marc (Beebe)

Would love to talk to you. We are related. Of course you wrote this ages ago but I thought I would try.

Alice

For Malcolm, who wanted more info on Beebe’s railcar:

There were actually 2 private cars owned by Beebe & his companion Charles Clegg. The older one, called the “Gold Coast,” was made of wood and is on display at the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento. The later, steel-sided car is called the “Virginia City” and is available for hire today. It is Amtrak-compliant and is used by people who want to travel the country in the kind of opulence Beebe once enjoyed.

http://portal.parks.ca.gov/CapitalDistrict/csrmdocentroundhouse/SitePages/Gold%20Coast%20Summary.aspx

http://www.vcrail.com/vchistory_railcars.htm

https://www.californiarailroad.museum/