Book Review of “The Life of George Brummell, Esq.” By Captain Jesse

Littell’s Living Age, 1844

Article unsigned

Why on earth was such a subject selected for two large octavo volumes? We suspect that Captain Jesse has greatly overrated the attraction of his hero.

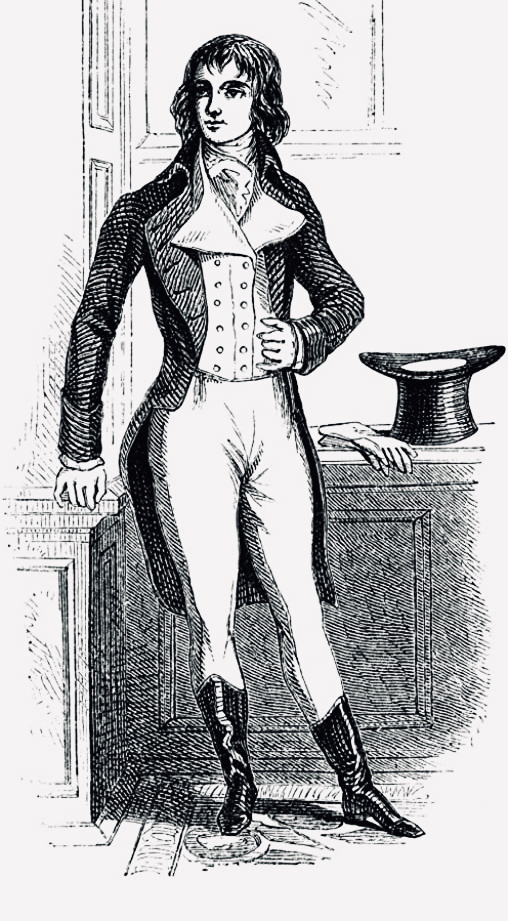

We never could find that Brummell’s usefulness went beyond the invention of the starched neckcloth, or that his genius amounted to more than an appalling impudence. It is clear that these two things made him the rage. The impudence was a thing sui generis and inimitable: a man who took down one of his sayings, to the very letter, would miss the whole effect in repeating it for want of his slow, deliberate, exquisite way. The starched neckcloth was in some cases achievable; and we believe, though the unsuccessful efforts of one aspirant certainly ended in suicide, that a great many people were thought to have succeeded in it. It was clear from the first that the Prince of Wales never could: his neck forbade the supposition. But unattainable neckcloths may have added in this quarter to Brummell’s influence. He dressed admirably in other respects — not at all like a beau. The ars celare artum was brought to perfection in the color and make of his clothes. It was his maxim that a man should never be remarked for what be wore, and he was an instance of that exquisite propriety.

With this knowledge of Brummell, we opened Capt. Jesse’s ponderous volumes. We felt how flat these things must look upon paper, and were doomed to no disappointment. Capt. Jesse hardly seems aware of it. He fights up gallantly against all his disadvantages, but it was not in the nature of things that he should master one of them. The life of Brummell should have been written in some fifty pages, by one of his companions, and issued for the use of what is called the fashionable world, and no other. There is no earthly meaning or moral in it for any other class. Rational people do not need to be told that if a man lives for mere sensual pleasures he had better die when the means of gratification are over; that if he gambles, he incurs the chance of losing; that if he cannot pay he must run; that to a fashionable man in this condition a fashionable friend is a rotten reed; and that the farce must tragically end in beggary, misery and starvation. We see no point for sympathy in any part of Brummell’s career. There is but a revolting selfishness from beginning to end. We see nothing that could have raised him into a reputable memory, but the fact of having lived three centuries since and pandered to Henry the Eighth instead of George the Fourth. He would nave served as good a master, and instead of the Court disgrace which left him to die in a madhouse, his days might have closed respectably on a scaffold.

His father’s career is accurately traced by Capt. Jesse. He was a protege of the first Lord Liverpool and for fifteen years Lord North’s private secretary. Baton, Oxford, a cornetcy in the Tenth Hussars, and 25,000 pounds were his youngest son’s introduction to the world. At 18 George Brummell was a captain, and at 20 had left the army. His London career, as chief of the dandies, lasted 18 years. He was but 38 when he fled to Calais in 1816.

Even in his ashes lived his wonted impudence. Nothing could quench it. His mode of life was pretty much the same for 12 or 14 years at Calais, as it had been in London (difference of place excepted!), though how he managed it, living on charity as he must have done, is difficult to divine. He denied himself no comfort, but was always whining and complaining: the last, indeed, was an addition to his luxuries. After a good dinner from Dessin’s, a bottle of Dorchester ale, a liqueur glass of brandy, and a bottle of Bordeaux, he would write to Lord Sefton that he was “lying on straw, and grinning through the bars of a gaol; eating bran bread, my good fellow, eating bran bread.” If he could have known how soon he would in sober sadness grin through real bars, and lie on veritable straw, it might have made even him serious.

The Whigs gave him the consulate of Caen in Normandy in 1830. It was worth 400 pounds a year, but he had to assign an annuity of 320 to his Calais creditors before he could have that place, and to content himself with the fiction of supporting his consulate on 80 pounds a year. Of course he was soon enormously in debt, cheating and starving his washerwoman first, as he had done at Calais, for starch continued to be his prime necessity. If anything could add to the repulsive picture of the man at this time, it would be the doleful Delia Cruscan letters he writes to young ladies, here printed by Capt. Jesse as worthy of preservation. He soon loses his consulate and is carried off to prison, and it will depend altogether on temperament whether the reader laughs or cries over his piercing shrieks from between his prison bars, that the pigeon they give him for dinner is a skeleton, that the mutton chops which support it are not larger than half a crown, that the biscuits are like a bad halfpenny, that he has but six potatoes, and that the cherries sent him for dessert are positively unripe.

So the man continues to the last. In paralysis, imprisonment and the apparent neighborhood of death, his chief anxiety is to get back to his five sous’ whist, and his greatest horror to seal a note with a wafer. Charitable supplies from England set him at liberty again, and on certain conditions there is reasonable prospects of charitable support for the rest of his days. But his spirit of self-sacrifice is quite exhausted when he has brought himself down to one complete change of linen daily. He cannot find it in his heart to renounce his primrose gloves, his Eau de Cologne, oil for his wigs, patent blacking for his boots, or an occasional cast of gambling in a lottery. For these luxuries be again runs into debt.

But we have now to note the end. In the winter of 1836 Brummell suddenly appeared in a black cravat. Starch and cambric had made him, and their absence denoted his ruin. His wits had begun to fail. In 1837 he was an idiot. His cleanliness and fastidious appetite, were replaced by — what Capt. Jesse should hardly have told. The blubber of the Esquimaux, the style of one of Swift’s Houhynhyms, may stand for these revolting details of the voracity and filth of Brummell. He died in the madhouse of Bon Succour in 1840.

Jesse writes:

“On certain nights some strange fancy would seize him, that it was necessary he should give a party, and he accordingly invited many of the distinguished persons with whom he had been intimate in former days, though some of them were already numbered with the dead.”

“On these gala evenings, he desired his attendant to arrange his apartment, set out a whist-table, and light the bougies (he burnt only tallow at the time), and at eight o’clock this man, to whom he had already given his instructions, opened wide the door of his sitting-room and announced the Duchess of Devonshire.”

“At the sound of her Grace’s well remembered name, the Beau, instantly rising from his chair, would advance towards the door, and greet the cold air from the staircase, as if it bad been the beautiful Georgiana herself. If the dust of that fair creature could have stood reanimate in all her loveliness before him, she would not have thought his bow less graceful than it had been thirty-five years before. For despite poor Brummcll’s mean habiliments and uncleanly person, the supposed visitor was received with all his former courtly ease of manner, and the earnestness that the pleasure of such an honor might be supposed to excite. ‘Ah! my dear Duchess,’ faltered the Beau, ‘how rejoiced I am to see you; so very amiable of you at this short notice! Pray bury yourself in this arm-chair; do you know it was a gift to me from the Duchess of York, who was a very kind friend of mine, but, poor thing, you know, she is now no more.’ Here the eyes of the old man would fill with the tears of idiocy, and, sinking into the fauteuil himself, he would sit for some time looking vacantly at the fire until Lord Alvanley, Worcester or any other old friend he chose to name was announced, when he again rose to receive them and went through a similar pantomime. At ten his attendant announced the carriages — and this farce was at an end.”

“I have deferred writing for some time, hoping to be able to inform you that I had succeeded in getting Mr. Brummell into one of the public institutions, but I am sorry to say that I have failed. I have also tried to get him into a private house, but no one will undertake the charge of him in his present state. In fact, it would be totally impossible for me to describe the dreadful situation he is in. For the last two months I have been obliged to pay a person to be with him night and day, and still we cannot keep him clean. He now lies upon a straw mattress, which is changed every day. They will not keep him at the hotel, and what to do I know not. I should think that some of his old friends in England would be able to get him into some hospital where he could be taken care of for the rest of his days. I beg and entreat of you to get something done for him, for it is quite out of the question that he can remain where he is. The clergyman and physician here can bear testimony to the melancholy state of idiocy he is in.”

It would he unjust not to add that Capt. Jesse’s book has much amusing detail incidentally connected with the subject. Sketches of the beaus who preceded Brummell, and of the general society in which he flourished, are here and there happily done. There is much merit of this kind in the book.

A mesmerising piece… such a sad descent but there’s a few chuckles before the tale becomes hopelessly grim:

“Even in his ashes lived his wonted impudence. Nothing could quench it.”

An intriguing epitaph!