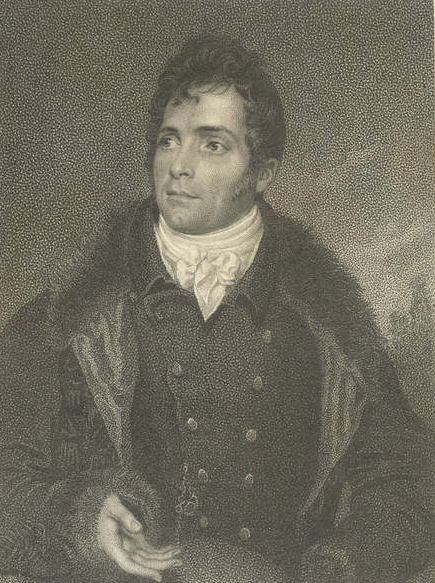

Romeo Coates

Romeo Coates

By Max Beerbohm, 1896

Even now Bath glories in his legend, not idly, for he was the most fantastic animal that ever stepped upon her pavement. Were ever a statue given him (and indeed he is worthy of a grotesque in marble), it would be put in Pulteney Street or the Circus. I know that the palm trees of Antigua overshadowed his cradle, that there must be even now in Boulogne many who set eyes on him in the time of his less fatuous declension, that he died in London. But Mr. Coates (for of that Romeo I write) must be claimed by none of these places. Bath saw the laughable disaster of his debut, and so, in a manner, his whole life seems to belong to her, and the story of it to be a part of her annals.

The Antiguan was already on the brink of middle-age when he first trod the English shore. But, for all his thirty-seven years, he had the heart of a youth, and his purse being yet as heavy as his heart was light, the English sun seemed to shine gloriously about his path and gild the letters of introduction that he scattered everywhere. Also, he was a gentleman of amiable, nearly elegant mien, and something of a scholar. His father had been the most respectable resident Antigua could show, so that little Robert, the future Romeo, had often sat at dessert with distinguished travellers through the Indies. But in the year 1807 old Mr. Coates had died. As we may read in vol. lxxviii. of The Gentleman’s Magazine, “the Almighty, whom he alone feared, was pleased to take him from this life, after having sustained an untarnished reputation for seventy-three years,” a passage which, though objectionable in its theology, gives the true story of Romeo’s antecedents and disposes of the later calumnies that declared him the son of a tailor. Realising that he was now an orphan, an orphan with not a few grey hairs, our hero had set sail in quest of amusing adventure.

For three months he took the waters of Bath, unobtrusively, like other well-bred visitors. His attendance was solicited for all the most fashionable routs, and at assemblies he sat always in the shade of some titled turban. In fact, Mr. Coates was a great success. There was an air of most romantic mystery that endeared his presence to all the damsels fluttering fans in the Pump Room. It set them vying for his conduct through the mazes of the Quadrille or of the Triumph, and blushing at the sound of his name. Alas! their tremulous rivalry lasted not long. Soon they saw that Emma, sole daughter of Sir James Tylney Long, that wealthy baronet, had cast a magic net about the warm Antiguan heart. In the wake of her chair, by night and day, Mr. Coates was obsequious. When she cried that she would not drink the water without some delicacy to banish the iron taste, it was he who stood by with a box of vanilla-rusks. When he shaved his great moustachio, it was at her caprice. And his devotion to Miss Emma was the more noted for that his own considerable riches were proof that it was true and single. He himself warned her, in some verses written for him by Euphemia Boswell, against the crew of penniless admirers who surrounded her:

Lady, ah! too bewitching lady! now beware

Of artful men that fain would thee ensnare

Not for thy merit, but thy fortune’s sake.

Give me your hand — your cash let venals take.

Miss Emma was his first love. To understand his subsequent behaviour, let us remember that Cupid’s shaft pierces most poignantly the breast of middle-age. Not that Mr. Coates was laughed at in Bath for a love-a-lack-a-daisy. On the contrary, his mien, his manner, were as yet so studiously correct, his speech so reticent, that laughter had been unusually inept. The only strange taste evinced by him was his devotion to theatricals. He would hold forth, by the hour, upon the fine conception of such parts as Macbeth, Othello and, especially, Romeo. Many ladies and gentlemen were privileged to hear him recite, in this or that drawing-room, after supper. All testified to the real fire with which he inflamed the lines of love or hatred. His voice, his gesture, his scholarship, were all approved. A fine symphony of praise assured Mr. Coates that no suitor worthier than he had ever courted Thespis. The lust for the footlights’ glare grew lurid in his mothish eye. What, after all, were these poor triumphs of the parlour? It might be that contemptuous Emma, hearing the loud salvos of the gallery and boxes, would call him at length her lord.

At this time there arrived at the York House Mr. Pryse Gordon, whose memoirs we know. Mr. Coates himself was staying at number 88 Gay Street, but was in the habit of breakfasting daily at the York House, where he attracted Mr. Gordon’s attention by “rehearsing passages from Shakespeare, with a tone and gesture extremely striking both to the eye and the ear.” Mr. Gordon warmly complimented him and suggested that he should give a public exposition of his art. The cheeks of the amateur flushed with pleasure. “I am ready and willing,” he replied, “to play ‘Romeo’ to a Bath audience, if the manager will get up the play and give me a good ‘Juliet’; my costume is superb and adorned with diamonds, but I have not the advantage of knowing the manager, Dimonds.” Pleased by the stranger’s ready wit, Mr. Gordon scribbled a note of introduction to Dimonds there and then. So soon as he had “discussed a brace of muffins and so many eggs,” the new Romeo started for the playhouse, and that very day bills were posted to the effect that “a Gentleman of Fashion would make his first appearance on February 9 in a role of Shakespeare.” All the lower boxes were immediately secured by Lady Belmore and other lights of Bath. “Butlers and Abigails,” it is said, “were commanded by their mistresses to take their stand in the centre of the pit and give Mr. Coates a capital, hearty clapping.” Indeed, throughout the week that elapsed before the premiere, no pains were spared in assuring a great success. Miss Tylney Long showed some interest in the arrangements. Gossip spoke of her as a likely bride.

The night came. Fashion, Virtue, and Intellect thronged the house. Nothing could have been more cordial than the temper of the gallery. All were eager to applaud the new Romeo. Presently, when the varlets of Verona had brawled, there stepped into the square — what! — a mountebank, a monstrosity. Hurrah died upon every lip. The house was thunderstruck. Whose legs were in those scarlet pantaloons? Whose face grinned over that bolster-cravat, and under that Charles II wig and opera-hat? From whose shoulders hung that spangled sky-blue cloak? Was this bedizened scarecrow the Amateur of Fashion, for sight of whom they had paid their shillings? At length a voice from the gallery cried, “Good evening, Mr. Coates,” and, as the Antiguan —- for he it was — bowed low, the theatre was filled with yells of merriment. Only the people in the boxes were still silent, staring coldly at the protegé had played them so odious a prank. Lady Belmore rose and called for her chariot. Her example was followed by several ladies of rank. The rest sat spellbound, and of their number was Miss Tylney Long, at whose rigid face many glasses were, of course, directed. Meanwhile the play proceeded. Those lines that were not drowned in laughter Mr. Coates spoke in the most foolish and extravagant manner. He cut little capers at odd moments. He laid his hand on his heart and bowed, now to this, now to that part of the house, always with a grin. In the balcony-scene he produced a snuff-box, and, after taking a pinch, offered it to the bewildered Juliet. Coming down to the footlights, he laid it on the cushion of the stage-box and begged the inmates to refresh themselves, and to “pass the golden trifle on.” The performance, so obviously grotesque, was just the kind of thing to please the gods. The limp of Hephaestus could not have called laughter so unquenchable from their lips. It is no trifle to set Englishmen laughing, but once you have done it, you can hardly stop them. Act after act of the beautiful love-play was performed without one sign of satiety from the seers of it. The laughter rather swelled in volume. Romeo died in so ludicrous a way that a cry of “encore” arose and the death was actually twice repeated. At the fall of the curtain there was prolonged applause. Mr. Coates came forward, and the good-humoured public pelted him with fragments of the benches. One splinter struck his right temple, inflicting a scar, of which Mr. Coates was, in his old age, not a little proud. Such is the traditional account of this curious debut. Mr. Pryse Gordon, however, in his memoirs tells another tale. He professes to have seen nothing peculiar in Romeo´s dress, save its display of fine diamonds, and to have admired the whole interpretation. The attitude of the audience he attributes to a hostile cabal. John R. and Hunter H. Robinson, in their memoir of Romeo Coates, echo Mr. Pryse Gordon’s tale. They would have done well to weigh their authorities more accurately.

I had often wondered at this discrepancy between document and tradition. Last spring, when I was in Bath for a few days, my mind brooded especially on the question. Indeed, Bath, with her faded memories, her tristesse, drives one to reverie. Fashion no longer smiles from her windows nor dances in her sunshine, and in her deserted parks the invalids build up their constitutions. Now and again, as one of the frequent chairs glided past me, I wondered if its shadowy freight were the ghost of poor Romeo. I felt sure that the traditional account of his début was mainly correct. How could it, indeed, be false? Tradition is always a safer guide to truth than is the tale of one man. I might amuse myself here, in Bath, by verifying my notion of the debut or proving it false.

One morning I was walking through a narrow street in the western quarter of Bath, and came to the window of a very little shop, which was full of dusty books, prints and engravings. I spied in one corner of it the discoloured print of a queer, lean figure, posturing in a garden. In one hand this figure held a snuff-box, in the other an opera-hat. Its sharp features and wide grin, flanked by luxuriant whiskers, looked strange under a Caroline wig. Above it was a balcony and a lady in an attitude of surprise. Beneath it were these words, faintly lettered: “Bombastes Coates wooing the Peerless Capulet, that’s ‘nough (that snuff) 1809.” I coveted the print. I went into the shop.

A very old man peered at me and asked my errand. I pointed to the print of Mr. Coates, which he gave me for a few shillings, chuckling at the pun upon the margin.

“Ah,” he said, “they’re forgetting him now, but he was a fine figure, a fine sort of figure.”

“You saw him?”

“No, no. I’m only seventy. But I’ve known those who saw him. My father had a pile of such prints.”

“Did your father see him?” I asked, as the old man furled my treasure and tied it with a piece of tape.

“My father, sir, was a friend of Mr. Coates,” he said. “He entertained him in Gay Street. Mr. Coates was my father’s lodger all the months he was in Bath. A good tenant, too. Never eccentric under my father’s roof — never eccentric.”

I begged the old bookseller to tell me more of this matter. It seemed that his father had been a citizen of some consequence, and had owned a house in modish Gay Street, where he let lodgings. Thither, by the advice of a friend, Mr. Coates had gone so soon as he arrived in the town, and had stayed there down to the day after his debut, when he left for London.

“My father often told me that Mr. Coates was crying bitterly when he settled the bill and got into his travelling-chaise. He’d come back from the playhouse the night before as cheerful as could be. He’d said he didn’t mind what the public thought of his acting. But in the morning a letter was brought for him, and when he read it he seemed to go quite mad.”

“I wonder what was in the letter!” I asked. “Did your father never know who sent it?”

“Ah,” my greybeard rejoined, “that’s the most curious thing. And it’s a secret. I can’t tell you.”

He was not as good as his word. I bribed him delicately with the purchase of more than one old book. Also, I think, he was flattered by my eager curiosity to learn his long-pent secret. He told me that the letter was brought to the house by one of the footmen of Sir James Tylney Long, and that his father himself delivered it into the hands of Mr. Coates.

“When he had read it through, the poor gentleman tore it into many fragments, and stood staring before him, pale as a ghost. ‘I must not stay another hour in Bath,’ he said. When he was gone, my father (God forgive him!) gathered up all the scraps of the letter, and for a long time he tried to piece them together. But there were a great many of them, and my father was not a scholar, though he was affluent.”

“What became of the scraps?” I asked. “Did your father keep them?”

“Yes, he did. And I used to try, when I was younger, to make out something from them. But even I never seemed to get near it. I’ve never thrown them away, though. They’re in a box.”

I got them for a piece of gold that I could ill spare — some score or so of shreds of yellow paper, traversed with pale ink. The joy of the archaeologist with an unknown papyrus, of the detective with a clue, surged in me. Indeed, I was not sure whether I was engaged in private inquiry or in research; so recent, so remote was the mystery. After two days labour, I marshalled the elusive words. This is the text of them:

MR. COATES, SIR,

They say Revenge is sweet. I am fortunate to find it is so. I have compelled you to be far more a Fool than you made me at the fete-champetre of Lady B. & I, having accomplished my aim, am ready to forgive you now, as you implored me on the occasion of the fete. But pray build no Hope that I, forgiving you, will once more regard you as my Suitor. For that cannot ever be. I decided you should show yourself a Fool before many people. But such Folly does not commend your hand to mine. Therefore desist your irksome attention &, if need be, begone from Bath. I have punished you, & would save my eyes the trouble to turn away from your person. I pray that you regard this epistle as privileged and private.

E. T. L. 10 of February.

The letter lies before me as I write. It is written throughout in a firm and very delicate Italian hand. Under the neat initials is drawn, instead of the ordinary flourish, an arrow, and the absence of any erasure in a letter of such moment suggests a calm, deliberate character and, probably, rough copies. I did not, at the time, suffer my fancy to linger over the tessellated document. I set to elucidating the reference to the fete-champetre. As I retraced my footsteps to the little bookshop, I wondered if I should find any excuse for the cruel faithlessness of Emma Tylney Long.

The bookseller was greatly excited when I told him I had re-created the letter. He was very eager to see it. I did not pander to his curiosity. He even offered to buy the article back at cost price. I asked him if he had ever heard, in his youth, of any scene that had passed between Miss Tylney Long and Mr. Coates at some fete-champetre. The old man thought for some time, but he could not help me. Where then, I asked him, could I search old files of local newspapers? He told me that there were supposed to be many such files mouldering in the archives of the Town Hall.

I secured access, without difficulty, to these files. A whole day I spent in searching the copies issued by this and that journal during the months that Romeo was in Bath. In the yellow pages of these forgotten prints I came upon many complimentary allusions to Mr. Coates : “The visitor welcomed (by all our aristocracy) from distant Ind,” “the ubiquitous,” “the charitable riche.” Of his “forthcoming impersonation of Romeo and Juliet” there were constant puffs, quite in the modern manner. The accounts of his debut all showed that Mr. Pryse Gordon’s account of it was fabulous. In one paper there was a bitter attack on “Mr. Gordon, who was responsible for this insult to Thespian art, the gentry, and the people, for he first arranged the whole production” — an extract which makes it clear that this gentleman had a good motive for his version of the affair.

But I began to despair of ever learning what happened at the fete-champetre. There were accounts of “a grand garden-party, whereto Lady Belper, on March the twenty-eighth, invited a host of fashionable persons.” The names of Mr. Coates and of “Sir James Tylney Long and his daughter” were duly recorded in the lists. But that was all. I turned at length to a tiny file, consisting of five copies only, Bladud’s Courier. Therein I found this paragraph, followed by some scurrilities which I will not quote:

Mr. Coates, who will act Romeo (Wherefore art thou Romeo?) this coming week for the pleasure of his fashionable circle, incurred the contemptuous wrath of his Lady Fair at the Fete. It was a sad pity she entrusted him to hold her purse while she fed the gold-fishes. He was very proud of the honour till the gold fell from his hand among the gold-fishes. How appropriate was the misadventure! But Miss Black Eyes, angry at her loss and her swain’s clumsiness, cried: ‘Jump into the pond, sir, and find my purse instanter!’ Several wags encouraged her, and the ladies were of the opinion that her adorer should certainly dive for the treasure. ‘Alas,’ the fellow said, ‘I cannot swim, Miss. But tell me how many guineas you carried and I will make them good to yourself.’ There was a great deal of laughter at this encounter, and the haughty damsel turned on her heel, nor did shoe vouchsafe another word to her elderly lover.

‘When recreant man

Meets lady’s wrath, &c. &c.’

So the story of the debut was complete! Was ever a lady more inexorable, more ingenious, in her revenge? One can fancy the poor Antiguan going to the Baronet’s house next day with a bouquet of flowers and passionately abasing himself, craving her forgiveness. One can fancy the wounded vanity of the girl, her shame that people had mocked her for the disobedience of her suitor. Revenge, as her letter shows, became her one thought. She would strike him through his other love, the love of Thespis. “I have compelled you,” she wrote afterwards, in her bitter triumph, “to be a greater Fool than you made me.” She, then, it was that drove him to his public absurdity, she who insisted that he should never win her unless he sacrificed his dear longing for stage-laurels and actually pilloried himself upon the stage. The wig, the pantaloons, the snuff-box, the grin, were all conceived, I fancy, in her pitiless spite. It is possible that she did but say: “The more ridiculous you make yourself, the more hope for you.” But I do not believe that Mr. Coates, a man of no humour, conceived the means himself. They were surely hers.

It is terrible to think of the ambitious amateur in his bedroom, secretly practising hideous antics or gazing at his absurd apparel before a mirror. How loath must he have been to desecrate the lines he loved so dearly and had longed to declaim in all their beauty and their resonance! And then, what irony at the daily rehearsal! With how sad a smile must he have received the compliments of Mr. Dimonds on his fine performance, knowing how different it would all be on the night! Nothing could have steeled him to the ordeal but his great love. He must have wavered, had not the exaltation of his love protected him. But the jeers of the mob were music in his hearing, his wounds love-symbols. Then came the girl’s cruel contempt of his martyrdom.

Aphrodite, who has care of lovers, did not spare Miss Tylney Long. She made her love, a few months after, one who married her for her fortune and broke her heart. In years of misery the wayward girl worked out the penance of her unpardonable sin, dying, at length, in poverty and despair. Into the wounds of him who had so truly loved her was poured, after a space of fourteen years, the balsam of another love. On the 6th September 1823, at St. George’s, Hanover Square, Mr. Coates was married to Miss Anne Robinson, who was a faithful and devoted wife to him till he died.

Meanwhile, the rejected Romeo did not long repine. Two months after the tragedy at Bath, he was at Brighton, mingling with all the fashionable folk, and giving admirable recitations at routs. He was seen every day on the Parade, attired in an extravagant manner, very different to that he had adopted in Bath. A pale-blue surtout, tasselled Hessians, and a cocked hat were the most obvious items of his costume. He also affected a very curious tumbril, shaped like a shell and richly gilded. In this he used to drive around, every afternoon, amid the gapes of the populace. It is evident that, once having tasted the fruit of notoriety, he was loath to fall back on simpler fare. He had become a prey to the love of absurd ostentation. A lively example of dandyism unrestrained by taste, he parodied in his person the foibles of Mr. Brummell and the King. His diamonds and his equipage and other follies became the gossip of every newspaper in England. Nor did a day pass without the publication of some little rigmarole from his pen. Wherever there was a vacant theatre — were it in Cheltenham, Birmingham, or any other town — he would engage it for his productions. One night he would play his favourite part, Romeo, with reverence and ability. The next, he would repeat his first travesty in all its hideous harlequinade. Indeed, there can be little doubt that Mr. Coates, with his vile performances, must be held responsible for the decline of dramatic art in England and the invasion of the amateur. The sight of such folly, strutting unabashed, spoilt the prestige of the theatre. To-day our stage is filled with tailors’ dummy heroes, with heroines who have real curls and can open and shut their eyes and, at a pinch, say “mamma” and “papa.” We must blame the Antiguan, I fear, for their existence. It was he — the rascal — who first spread that scenae sacra fames. Some say that he was a schemer and impostor, feigning eccentricity for his private ends. They are quite wrong; Mr. Coates was a very good man. He never made a penny out of his performances; he even lost many hundred pounds. Moreover, as his speeches before the curtain and his letters to the papers show, he took himself quite seriously. Only the insane take themselves quite seriously.

It was the unkindness of his love that maddened him. But he lived to be the lightest-hearted of lunatics and caused great amusement for many years. Whether we think of him in his relation to history or psychology, dandiacal or dramatic art, he is a salient, pathetic figure. That he is memorable for his defects, not for his qualities, I know. But Romeo, in the tragedy of his wild love and frail intellect, in the folly that stretched the corners of his “peculiar grin” and shone in his diamonds and was emblazoned upon his tumbril, is more suggestive than some sages. He was so fantastic an animal that Oblivion were indeed amiss. If no more, he was a great Fool. In any case, it would be fun to have seen him.