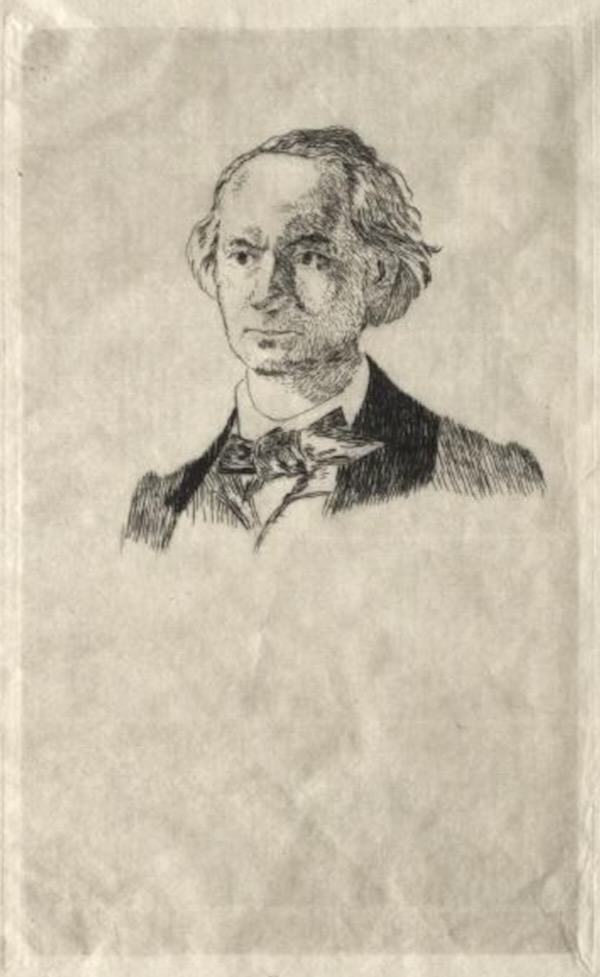

Charles Baudelaire

By Theophile Gautier, 1867

Although his existence was short — he lived scarce forty-six years — Charles Baudelaire had time to assert himself, and to write his name upon that wall of the nineteenth century, inscribed already with so many signatures, destined to endure. Do not doubt that his will remain there, for it represents an original and powerful talent, disdainful to excess of those feudal services which make popularity easy, loving only the rare, the difficult and the strange, possessed of an elevated literary conscience; amid the necessities of life, abandoning a work only when he believed it perfect, weighing every word as misers might weigh a suspected ducat, revising a proof ten times, submitting the poet in him to the must subtile criticism, and with unwearying effort, seeking the particular ideal he had formed for himself.

Born in India, and thoroughly acquainted with the English language, he made his debut by translations from Edgar Poe, so excellent that they seemed original works, and made the thought of the author gain in passing from one idiom to the other. Baudelaire has naturalized in France that imaginative mind so wildly grotesque, and so bizarre, that compared with it Hoffmann is no more than a fantastic Paul de Kock. Thanks to Baudelaire, we have had the surprise of a literary flavor totally unknown. Our intellectual palate has been astonished, as when at the Universal Exposition, we drank some of those American draughts, a foaming mixture of ice, soda water, ginger and other exotic ingredients. Into what giddy intoxication we were thrown by reading the “Golden Bug,” the “Usher House,” “The Case of Mr. Waldemar,” “King Pestilence,” the “Monosuna” — all those extraordinary histories! These fantastic tales excited public curiosity to the highest pitch, and the name of Baudelaire became, in some sort, inseparable from the name of the American author.

These translations were preceded by a most interesting study upon Edgar Poe from a biographical and metaphysical point of view. One could not in a more subtle manner analyze this genius of an eccentricity which almost seemed to border upon madness, and whose groundwork is a pitiless logic, pushing the consequences of an idea to their end. This blending of passion and coldness, of intoxication and mathematical processes, this keen raillery intermixed with lyric effusions of the highest poetry, were admirably comprehended by Baudelaire. He was seized with the most lively sympathy for this haughty and eccentric character, which so much shocked American cant — a disagreeable variety of English cant — and frequent communion with this giddy intellect exercised a great influence upon him.

Edgar Poe was not merely a recounter of extraordinary stories, a journalist whom no one surpassed in the art of launching a scientific canard, a mystifier par excellence of open-mouthed credulity — he was also an Aesthetician of the highest power, a great poet of a very refined and very complicated sort. His poem of “The Raven,” through a gradation of strophes, and the disquieting persistence of the refrain, reaches an intense but melancholy effect, a terror and a fatal presentiment against which it is difficult to defend one’s self. It is doing no wrong to the originality of Baudelaire to say that we find in his “Flowers of Evil,” a sort of reflection of the mysterious manners of Edgar Poe, on a groundwork of romantic color.

Some years ago, as it is not our habit to wait until our friends are dead to praise them, we wrote a notice of Baudelaire, published as a preface to some extracts from his poems, inserted in a collection of French Poets, where may be found this passage upon the “Fleurs de Mal,” the author’s most important and most original work. This page cannot by suspected of posthumous complaisance, and what we have said of the living poet, we can report of the dead poet, so prematurely and so unhappily taken from us:

We read in the tales of Nathaniel Hawthorne, the description of a singular garden, where a toxicologic botanist has reunited the flora of venomous plants. These plants, of strangely disheveled foliage, of a black or mineral glaucous green, as if tinged by the sulphate of copper, have a sinister and formidable beauty. We feel them dangerous, despite their charm; they have in their haughty, provoking or perfidious attitude, the consciousness of an immense power, or of an irresistible seduction. From their flowers, savagely variegated and mottled, of a purple similar to congealed blood, or of a chlorotic white, they exhale, sharp, penetrating, intoxicating odors. In their poisoned chalices, the dew changes into aqua toffana, and there flit around them, only cantharides cuirassed in golden green, or flies of a steel-blue, whose prick causes carbuncles (le charbon). The milk-wort, the aconite, the henbane, the hemlock, mingle their cold virus with the glowing poisons of the tropics and the Indies. The manchineel here displays its small apples, deadly as those which hang from the tree of knowledge, the upas here distils its lacteous juices, more corrosive than aquafortis. Above this garden floats a sickly vapor, which benumbs the birds when they pass through it. But the doctor’s daughter lives unharmed amid these mephitic effluvias. Her lungs without danger breathe this air where any other than she and her father would inhale certain death. She makes for herself bouquets of the flowers, she adorns her hair with them, she perfumes her breast with them, she nibbles at their petals as young girls nibble at roses. Slowly saturated with the venomous juices, she has herself become a living poison which neutralizes all other poisons. Her beauty, like that of the plants of her garden, has something disquieting, fatal and morbid. Her hair, of a bluish-black, contrasts in a sinister way, with her complexion, of a dull, greenish pallor, from whence her mouth gleams forth, empurpled, one might say, by some bloody berry. An insane smile reveals teeth enshrined in a sombre red, and her fixed eyes fascinate like those of serpents. You would say she was one of those Javanaise, those love-vampyres, those nocturnal demons, whose passion in a fortnight exhausts the blood, the marrow and the soul of a European. And yet, she is a virgin, this doctor’s daughter, and languishes in solitude. Love tries in vain to become acclimated in this atmosphere, out of which she cannot live.

We have never read the “Fleurs de Mal” of Charles Baudelaire without thinking involuntarily, of this story of Hawthorne’s; they have these sombre and metallic colors, these greenish-gray leaves, and these death bringing odors. His muse resembles the doctor’s daughter, whom no poison can affect, but whose complexion in its bloodless pallor betrays the surroundings amid which she dwells.

This comparison pleased Baudelaire, and he loved to recognize in it the personification of his talent. He glorified himself also with this phrase of a great poet; “You invest the heaven of art, with we know not what deadly rays; you create a new shudder.”

But it would be committing a grave error to believe that amid these mandragores, these poppies, these poisonous blossoms, we may not meet here and there, a fresh rose of innoxious perfume, a large Indian flower opening its white chalice to the pure dew of heaven. When Baudelaire depicts the deformities of humanity and of civilization, it is only with a secret horror. He has no complaisance for them, he regards them as infractions of the universal rhythm. When he has been represented as immoral, a great word they know how to use in France as in America, he has been as astonished as if he heard them praise the virtue of the jasmine, and stigmatize the wickedness of the acrid ranunculus.

Beside the “Extraordinary Histories” of Edgar Poe, Baudelaire has translated from the same author, the “Adventures of Allen Gordon Pym,” which end with that horrible ingulfment in the vortex of the South Pole. He has also rendered into French, a cosmogonic dream entitled, “Eureka,” where the American author, planting himself upon the celestial mechanism of La Place, seeks to divine the secret of the universe, and believes he has found it. The difficulties encountered in the translation of such a work, may well be imagined. Under the title of “The Artificial Paradise,” Baudelaire has given us the substance of this work, blending with his own reflections, those of DeQuincy the English opium eater; and of the whole he has made a sort of treatise, which in many places, must run counter to Balzac’s famous theory of stimulants. It is more curious reading, illuminated by the phantasmagoria of opium, and a portraiture of the most brilliant, whimsical and terrible hallucinations, produced by this seducing poison, which, with its factitious happiness, stupefies China and the Orient. The author blames the man who seeks to withdraw himself from the fatality of sorrow, and lifts himself to an artificial paradise only to soon fall back into a deeper hell.

Baudelaire was an art-critic of perfect sagacity, and to the appreciation of painting he brought a metaphysical subtlety and an originality of perspective, which makes us regret that he had not devoted more time to this sort of work. The pages he has written upon Delacroix are among his most remarkable ones.

Toward the end of his life, he composed some short prose poems, but in rhythmed prose, wrought and polished like the most condensed poetry; they are strange fantasies, landscapes of the other world, unknown figures, which it seems to you he has seen elsewhere, spectral realities, and phantoms having a terrible reality. These pieces have appeared at hap-hazard, here and there, in divers reviews, and they should be reunited in a volume, adding to them others which the author must have preserved in his portfolio