The Golden Age of the Dandy

By John Peale Bishop

Vanity Fair, September 1920

The first dandy was, I suppose, the son of a Macaroni and, suffering from that Oedipus complex which afflicts all artists, he promptly proceeded to kill his father. At all events, the Macaroni, or Buck as he was commonly called in England, with his monstrously broad cocked hat, his oiled and stringy hair falling over his cheeks like a spaniel’s ears, his ineffable waistcoat and impossibly tight breeches, disappeared, no one knew quite where, shortly after the dandy stepped forth in polished boots and full trousers with a beaver over his ringleted hair.

If there were no further distinction between the buck and the dandy, they might safely be left to the limbo of forgotten fashion prints. But the difference between them is more than a mere matter of get-up, more than the oiling or curling of the hair. There is between them the difference of their respective ages: one “the great morning of the rights of man”, the other, the weary and cynical decade that followed the Congress of Vienna. The buck represented an exuberant, even eccentric, play of the individual at a time when the world seemed about to begin anew; the dandy an elegant and inessential gesture in a world where ennui had followed disillusion, where the last hope of human liberty had disappeared into the realm of lyrical drama, presided over by Percy Bysshe Shelley, where Childe Harold had become Don Juan. Dandyism was a meaningless protest against a life without meaning, a life ordered by a Hanoverian king with a fairly correct English accent and a German queen who played her tragic role with the finesse of a befurbelowed hausfrau. Therein lies all the difference between a dandy and the “smart” frippery of a Ward McAllister in an age of brownstone-front aristocrats.

Dandyism was not the invention of a single man, however much it has come to be associated with the name of George Brummell, King of the Dandies, “Roi par la grace de la Grace”. Its origin is not, properly speaking, English at all, for native English manners have always had something too much of the rigidity of the Puritan conscience and the heaviness of well-brewed stout. Its origin is to be found in the French influences which arrived in England with the Restoration of Charles II and continued until the Regency of George IV. The famous beaux of the XVIIth century — Sir Robert Fielding, Chesterfield, Bolingbroke, and Nash — all affected a piquant sumptuousness in attire, a preoccupation with effect, an elegant admission of vanity, distinctly reminiscent of the French court. French, too, was that feeling, for the romance of civilization, that formal crystallization of elaborate manners which characterized these men and their age. Somewhat later came the Macaronis, likewise touched with French ideas, expressing in extravagant and fantastic costume an individual revolt against established custom; but they were too essentially imitative of the effeminate fops of the Directoire to make a serious stir in British society. They but prepared the way for the dandy by adding a touch of colour to that period which King Alphonso XIII of Spain, as an accomplished and thoroughgoing dandy, occupies a position almost unique in the modern world, seems to belong neither to the XVIIIth nor the XIXth century, when the English sat in fear from the time when the Corsican first appeared in the uniform of a general of the Convention until finally their breath came more easily at the thought of Louis XVIII driving through a quieted Paris with a blue ribbon across the puffy expanse of his Bourbon bosom.

A heresy has long existed that the dandy was possessed of a consuming vanity, giving a meticulous attention to dress chiefly to win the notice and favours of women. As a matter of fact, the typical dandy cared far more for the gaming table than for such games of skill and chance as are played in the boudoir. Brummell himself allowed neither his heart nor his senses to interfere with his pose. In the latter days of his triumph he was accustomed to remain at a ball only long enough to make his effect and then disappear. The royal dandy, afterward George IV, spent his wedding night dining with his friends, leaving the disconsolate Caroline of Brunswick to a lonely meditation in German on her future career as queen of England.

As for the vanity of the dandy, it was vanity with a difference. He was concerned with the effect of his superior elegance upon others, because it was, after all, the only test of his success, but his vanity was satisfied in his being himself. Dandyism, as Barbey d’Aurevilly says, is something more than “the art of costume, a happy and audacious dictatorship in the matter of toilette and exterior elegance. Dandyism is a manner of being, entirely composed of nuances, which always appears in very old and very civilized societies, where comedy becomes rare and the proprieties scarcely triumph over boredom.” It was indeed a sumptuous attire masking the futility of life, a graceful and tragic gesture signifying disillusion. It is Brummell who remains the perfect type of dandy, because, apart from the perfection of his manner, his consummate taste in dress and the insolence of his wit, he cannot be said to exist. And yet it was no other than Byron who said he would rather be Brummell than Napoleon.

It was only with such a man as Brummell, the grandson of a confectioner, who had successfully insulted the Prince Regent before he was thirty, that dandyism could reach its final perfection of form. But there were others who, beginning life as dandies, are now remembered for other reasons that the successful tying of a neck cloth. Byron made his first appearance in London as a dandy rather than as a poet. Thomas Moore, the Irish poet, was a member of Watier’s, the club most frequented of the dandies, while Sheridan of “The Rivals” was not unknown there. Geroge IV himself aspired to be a dandy and at the corpulent end of his reign used to have the suits of his more slender days brought out for him to touch, recalling with anecdote and queasy sentiment the affairs at which they had first been seen. There were others, too, who gave their more serious moments to politics or the army — Alvanley, Worcester, Erskine, Craven, Yarmouth – but they survive only in Burke’s Peerage and a few unread memoirs.

Finally, the pleasant interlude came to an an end. George IV became fat — a sort of gastronomic suicide for a dandy — and Brummell’s insolence went to the point of referring to him as Big Ben, the familiar name of the prodigious footman at Carlton House.

So Brummell shortly betook himself to Calais, never again to set foot on English soil. George, on the other hand, became still fatter and shut Leigh Hunt in prison for referring to him as a “fat Adonis of fifty”. Finally, he refused to be seen and drove abroad only in a closed carriage, through whose curtained windows passers-by occasionally glimpsed the scarlet-faced obesity that had once been crowned king of England. The Golden Age of the Dandies was over.

There was a sort of brief Silver Age under William IV. Count Alfred d’Orsay, a son of one of Napoleon’s marshals, attempted to rule in Brummell’s stead. A brief arbiter of fashion he might have been, but this “Cupidon de chainé”, as Byron called him, was no fit successor to the cold and superbly insolent Brummell. He was too French, too humane, too amiable. At best he was a lion, at his worst a fop. Disraeli described him in the Count Alcibiades de Mirabel of his “Henrietta Temple” — a novel which appeared about the same time that the future Prime Minister of England burst upon an astonished Regent Street in a black velvet surtout, trousers of purple with broad gold stripes at their seams and a scarlet waistcoat. He himself describes his progress between two lines of gaping spectators as like that of the Israrelites passing between the walls of the Red Seas. Which shows that the dandies no longer enjoyed their former popular approval. Yet even so serious-minded a young man as Robert Browning was still able to present himself in ringlets and yellow gloves.

But the reign of the dandies was over. The young queen was about to ascend the throne and bring in a long regime of domestic virtue. Side whiskers, black broadcloth and checked trousers laid a sober and genteel siege to languishing young ladies on haircloth sofas. Life, which had been so cooly ironic, so exquisitely vain, became a matter of high-minded seriousness and satisfied contemplation of the new mechanical industrialism, the British aristocracy and a beneficent evolution, moving, none knew how, but quiety and to the measures of a Tennysonian recital toward “one far off, divine event.”

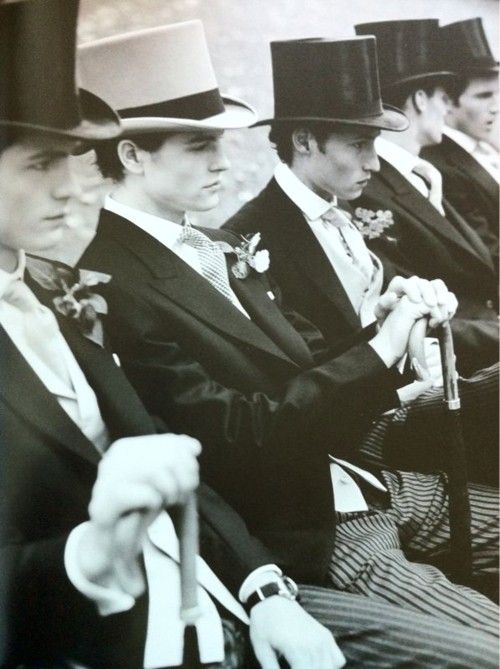

So the XIXth century moved to its close, pervaded by only one characteristic of dandyism — extreme self-satisfaction in its own perfections. Its garments, which had begun with a sort of democratic concealment alike of well turned leg and shrivelled shank, ended by making both cylindrical and ugly. King Edward VII, as Prince of Wales, was a limited arbiter of fashion, who occasionally caught something of the true manner of the dandy. But time and circumstance were against him. His only success in relieving the general ill-grace of the period was his revival of small clothes for formal court dress.

Toward the end of the century came the Aesthetes, with Oscar Wilde at their head. Lily in hand, one eye cast wistfully toward the faded beauty of the Pre-Raphaelites, the other craftily set on publicity, he made a brief march down Pall Mall. But Wilde not only lacked the necessary taste, he violated the first principles of dandyism, which is to move with superior grace in a circle limited by convention. The successor of Brummell,when he comes, will accomplish his purpose, not through violent changes, but through a series of minute modifications of the prevailing habits.

Almost the only man living who successfully recalls the grand manner of the Regency is not an Englishman at all, but a Spaniard, in fact the King of the Spaniards. His success as a dandy is probably due not so much to an infallible taste as to his lonely position in a society very old and very complicated with aristocratic traditions.

To speak now of a Beau or a Blood, an Incroyable or a Dandy, is to evoke a smile. The man who first used starch for a neckcloth is dismissed with a sneer, while the man who invented the patent machine for taking out potato eyes is hailed as a benefactor of his country. Let who will erect statues to the useful citizens who create a demand for useless appliances, who discover a later and dryer form of breakfast food, who add 57 new varieties of pickles to the already superfluous 57. I shall not subscribe. I shall save my pennies to buy a hand-carved snuff-box and, having bought it, remember between sneezes the men who regarded living as an art; possibly, since life seemed to them useless, as a fine art.