Dandyism As Spiritual Path

By Christian Chensvold

From “The Philosophy Of Style,” 2023

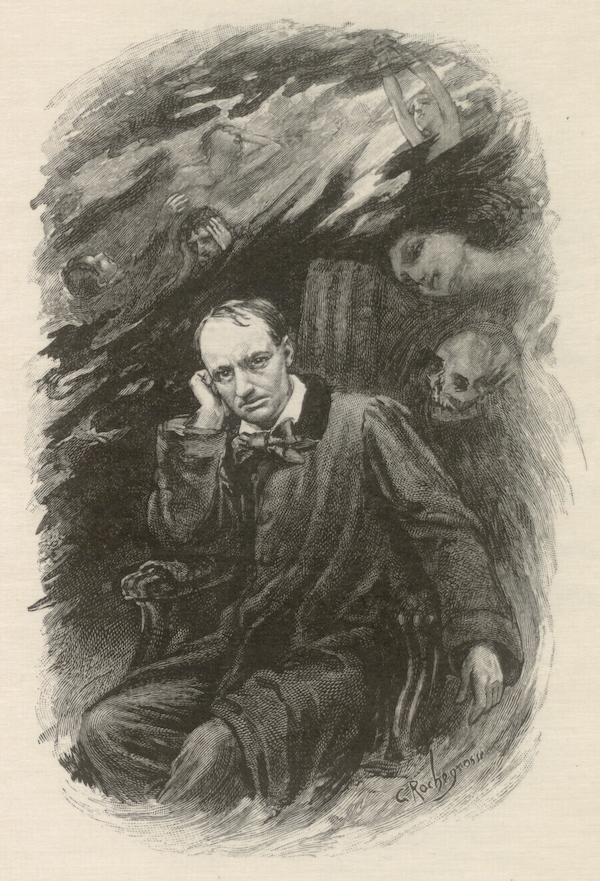

Can dandyism actually serve as a spiritual path, guiding us through the modern world with as much poise as possible in these troubled times? Let us look with freshly bloodshot eyes upon one of the foundational texts on which the entire tradition hangs: Baudelaire’s 1863 essay “The Dandy,” in which the poet likens dandyism to a kind of religion, calling it “a strange kind of spirituality” with punctilious rites as arcane as those of dueling.

In the century and a half since Baudelaire penned his musings, Friedrich Nietzsche proclaimed God dead, and one can hardly argue. The eclipsing of the divine took with it not only devotional faith, but also the sacred science of metaphysics. The ordering force known as Tradition, which gave form to the world’s great civilizations, has dimmed to the point where only a glimmer of light remains, but a glimmer that refuses to be extinguished. “Dandyism is like a setting sun,” writes Baudelaire, “without warmth and full of melancholy.” And so, amid the last rays of twilight, let us examine this “last flicker of heroism in times of decadence.”

Decadence is the winter of civilization — the Age of Iron according to Hesiod — an era of dissolution in which all contact with the divine origins has been lost. The temples are closed and the sages have gone into hiding. Only a faint fragrance, a wisp of the incense of olden times, floats in the air to guide the chosen few. In these dark times the Tradition has gone underground, and plays the passive role for active heroes to find it.

The quest to find its secret hiding place, to receive spiritual enlightenment and undergo the transformation it engenders, takes place entirely within the consciousness of the heroic seeker.

Just as religions have two sides — a metaphysical teaching for the regal and sacerdotal guardians, and a simplified version for the masses — Baudelaire’s essay displays an exoteric side ostensibly concerned with the charms of high life, and an inner esoteric teaching capable of being deciphered by spirit-seeking initiates.

Distilling the text down to only the esoteric passages, we end up with something like this:

Dandyism is a kind of aristocracy difficult to break down because it is founded on indestructible divine gifts. It is a doctrine, a monastic rule, a rigorous code to which certain disenchanted outsiders are strictly bound. Dandyism is a strange form of spirituality, almost a religion, fueled by a burning desire to create oneself, and stemming from an aristocratic superiority of mind.

Fueled by a latent fire, the dandy’s native energy is the source of his haughty, patrician attitude, aggressive even in its coldness.

Dandyism strengthens the will and schools the soul, bestowing a calmness revealing strength through risky sporting feats and a flawless dress of elegance and distinction. The dandy is a champion of pride who destroys triviality through opposition and revolt.

Dandyism is a setting sun, magnificent and full of melancholy. It is the last flicker of heroism in decadent ages, when democracy and egalitarianism are not yet all-powerful.

Baudelaire’s terse but illuminating language thus hints at a modern “mystery” of dandyism connecting it to earlier spiritual paths that have been rendered inaccessible in the age of decadence. Dandyism demands the adept synthesize all aspects of himself, from masculine audacity to feminine grace, and bring them under the dominion of a single authority: namely the spirit, or supra-personal dimension of himself. This force is then capable of dominating the weaker aspects of the personality, enabling the dandy to withstand the trials of life “like the Spartan bit by the fox.” It bestows a supernatural poise, attribute of a regal spiritual virility necessary for the superior being living in the age of mass recollectivization, when all values are materialistic and cater to mankind’s lower nature.

As a metaphysical path, dandyism is a late remnant of the heroic spiritual path of chivalry, which combined feats of courage and martial skill — Baudelaire’s “risky sporting feats” — with courtly graces. Winding back through time towards the origins, this path intersects with the Ars Regia or Royal Art, and from there to the Primordial Tradition, to mankind’s original archetypal unity and divine nobility, a state radiant of an otherworldly dignity no devotional piety can bestow.

Medieval chivalry was a heroic quest that unfolded against the backdrop of Christendom, rather than stemming from it. And while some knights were of noble birth, chivalry also opened the possibility of acquired nobility, in which the hero became a self-made aristocrat, though not in the courts and salons of patrician society, but in a spiritual realm outside of space and time. On the modern path, the hero is “a dandy in the process of becoming a clergyman,” as was said of the painter Fernand Khnopff.

The dandy’s cherished self-mastery — a quality Cicero called the highest human achievement — is the expression of an inner tension, a higher power acting upon the lower man, dominating his baser impulses and permeating his being with that invisible “certain something” mentioned by Barbey, which “introduces antique calm among our modern agitations,” and which Baudelaire likened to a “latent fire.”

One other matter remains, another link between the mystery of dandyism as a spiritual path and the Hermetic tradition of the Royal Art, and that is the figure of the hermaphrodite. This key symbol stands for the completion of the alchemical opus or Great Work, the restoration of the primordial state expounded by Plato, or the original double-sexed archetype of the human being created in God’s image. The medieval cycle of the Grail legend concerns the quest for the feminine vessel containing the “silvery, divine water” that confers immortality. This is the re-integration of the feminine principle into the hero, restoring his original wholeness and bringing fructifying fecundity to the arid kingdom of his life. Barbey d’Aurevilly, the first Frenchman to express the higher possibilities of dandyism, says dandies are, “Twofold and multiple natures, of an undecidely intellectual sex, their Grace is heightened by their Power, their Power by their Grace; they are the hermaphrodites of History, not of Fable.”

And so a tradition that began with George Brummell, which at its least was selfish frivolity and at its best staunch independence in the face of empire and revolution, became transformed into an initiatic path by Baudelaire, prophet of modernism and its discontents, with some help from his predecessor Barbey.

In the modern world, when all paths to discover and cultivate mankind’s divine nobility are closed, dandyism can indeed be seen as “the last stroke of heroism in times of decadence.” It is a newly forged path of an ancient journey, one that permits those rare few driven by an undaunted will to claim their God-given regal dignity.

That is an excellent piece

Thank you for this.